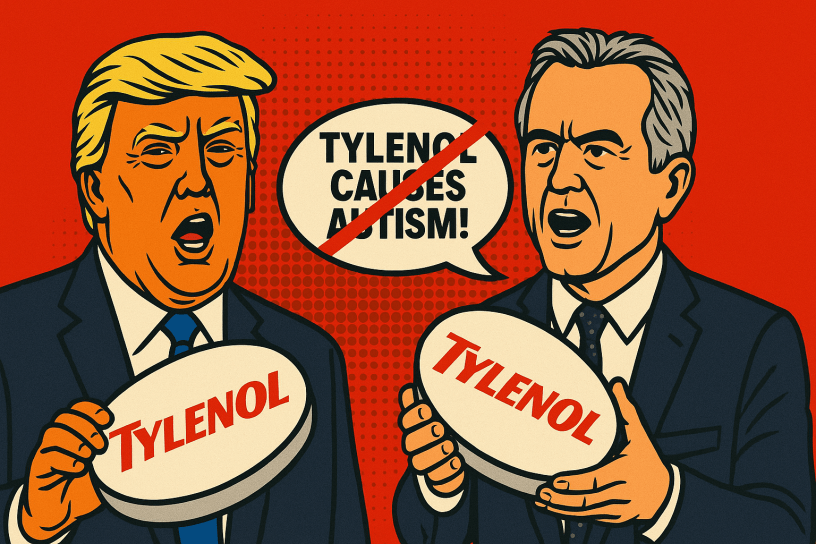

In September 2025, Donald Trump and Robert F. Kennedy Jr. made headlines by warning pregnant women and new parents against using Tylenol (acetaminophen). Their claim: Tylenol causes autism.

Then I got into an argument with someone on Twitter who kept saying the same thing basically. And they even brought “science” to the table. Here’s the deal: science should be left to scientists for a reason. My interaction with this individual is the perfect example of what RFK Jr. and Donald Trump do to twist reality, create disinformation, scare people, and gain votes.

To lend weight to the claims made, the person I talked to pointed to a recent study in Environmental Health that looked at acetaminophen use during pregnancy and childhood neurodevelopmental disorders. I do not know if the two NOT SCIENTISTS OR DOCTORS in charge did the same, if they hinted at the same study. But it is something that they would do and it shows what is wrong with what they are saying. The problem? The study doesn’t prove what they say it proves — and they know it.

You can read the study for yourself here: Environmental Health, 2025.

What the study actually found

The review analyzed 46 observational studies of prenatal acetaminophen use. Most showed a modest increase in risk of conditions like ADHD or autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The pooled odds ratio for ASD was about 1.19 — a small but statistically detectable association.

The key detail is that the data came from observational studies — research that looks at patterns in large populations but cannot prove that one thing directly causes another. In this case, mothers who took acetaminophen during pregnancy may also have had other factors — like fever, infection, or underlying health problems — that could themselves increase the risk of autism in their children. These are called confounders, and they make it impossible to draw a straight line from Tylenol to autism based on these studies alone.

The authors themselves were explicit about this. They acknowledged that while their findings showed a “consistent association,” residual confounding and biases could not be ruled out. In other words, the studies are useful for raising questions and encouraging more research, but they stop short of proving causation. That distinction is the foundation of evidence-based medicine — and the very part RFK Jr. and Trump leave out.

The exact quote from the study, by the authors, in conclusion:

“Our systematic review and meta-analysis found consistent evidence of an association between prenatal acetaminophen exposure and neurodevelopmental disorders, including ADHD and ASD. However, because all available studies were observational, we cannot exclude residual confounding and other biases. Therefore, while the evidence suggests a potential link, it does not prove causation. Given acetaminophen’s widespread use, we recommend cautious use during pregnancy—at the lowest effective dose and shortest possible duration, under medical supervision—until further high-quality research clarifies these risks.”

To put this into context, think of coffee. Decades of observational studies have linked coffee drinking with both increased and decreased risk of various conditions, depending on what’s being studied. But coffee does not simply “cause” or “prevent” disease. Instead, lifestyle factors, genetics, and many other variables come into play. The same logic applies here: seeing a pattern is not the same as proving a cause.

How RFK Jr. and Trump twist it

Kennedy and Trump collapse this nuance. They present “association” as if it were “proof.” By telling parents “Tylenol causes autism,” they weaponize fear, skipping over the messy scientific reality. It’s the same rhetorical trick anti-vaccine activists use: show people a study with complex caveats, then cherry-pick the scariest part while ignoring the authors’ caution.

This isn’t a new strategy. Kennedy has long framed himself as a crusader against mainstream science, taking ambiguous or preliminary findings and inflating them into definitive claims of danger. Trump, for his part, thrives on absolutes. “Don’t take Tylenol. Don’t take it.” That kind of blunt language carries weight politically, even if it runs directly counter to the nuance of scientific research.

By simplifying a careful meta-analysis into a soundbite, they transform the language of science into a political weapon. They’re not interested in what the researchers actually said; they’re interested in what their base wants to hear — a story about elites hiding the truth and ordinary people needing to “wake up.” In doing so, they erode the boundary between scientific caution and political fearmongering.

And the damage goes beyond rhetoric. Parents already struggling with fear and uncertainty about their children’s health are left more anxious. Some may avoid Tylenol even when it’s medically appropriate, or distrust doctors who recommend it. By twisting “association” into “causation,” Kennedy and Trump undermine medical trust at the very moment families need it most.

Why this matters

There’s a huge difference between acknowledging potential risks and declaring causation. Science is slow, careful, and self-correcting. Observational studies raise questions, but they do not settle them. By pretending otherwise, RFK Jr. and Trump erode trust in medicine and push parents toward unnecessary fear and confusion.

The real-world consequences of this can’t be overstated. When political leaders misuse scientific findings, it doesn’t just confuse the public — it reshapes behavior. We’ve already seen this play out with vaccines: rumors and distortions led to lower vaccination rates, outbreaks of preventable diseases, and greater strain on public health systems. The same could happen with common medications like Tylenol, if parents start avoiding them without medical reason.

It’s also worth remembering that acetaminophen has been widely used for decades and is one of the few fever reducers considered relatively safe in pregnancy when used as directed. The real health risk would come from leaving fevers untreated in pregnancy — since maternal fever itself is linked to negative developmental outcomes. In that sense, discouraging all Tylenol use could backfire, making the very problem Kennedy and Trump claim to be worried about even worse.

Finally, confusing correlation with causation corrodes the public’s ability to interpret science. When politicians play fast and loose with terms, they make it harder for people to tell the difference between preliminary evidence and proof. That erosion of trust doesn’t just affect debates about Tylenol — it ripples outward, weakening public confidence in everything from vaccines to climate science to food safety.

Conclusion

The trick isn’t in the science. It’s in how political figures like RFK Jr. and Donald Trump deliberately blur the line between association and causation to turn an ongoing scientific question into a soundbite.

Discover more from Adrian Cruce's Blog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.